Essential workers and small business owners are often at the forefront of the Covid-19 crisis – while health care workers, supermarket employees, and other essential workers keep society running during lockdowns, small business owners take the full force of the economic devestation firsthand.

As lockdown measures are lifted, concerns of a second wave of infections are on the minds of both groups, as they are once again at the heart of shaping and rebuilding communities. Feelings in Bushwick have been tinted with enthusiasm and a sense of hope for the future. Here in this piece, we speak with some of essential workers and business owners as they reflect on their experiences and share their takeaways from the last few months.

“I first sensed [the crisis] from the number of ambulances,” says Toby, a street vendor who sells records, jewelry, vintage T-shirts and other knick knacks on Wyckoff Avenue.

“My son is a firefighter and he would have to climb into people’s houses, where they might already be dead. He never really experienced anything like that. I guess, nobody really did,” he said.

Toby, who is a middle-aged man, told Bushwick Daily, while he hadn’t “really worried” about his own health during the outbreak in New York, he had been scared at the prospect of losing what he loves to do: shopping for items he knows people want.

“Like that book right?” he said pointing to the spot where I had watched a man buy a book from him, “I bought that book the day before yesterday. I only get stuff knowing people would want it and that’s very satisfying to me, you know?”

I did know. I had seen Toby on my weekend morning strolls on Wyckoff Avenue pre-coronavirus, standing over his table and rearranging his items to show off his best finds. After grabbing a warm cup of coffee from Starr Coffee, I would peruse his items, then go off to do my grocery shopping, a ritual that I remembered fondly during my “walks of the day” in quarantine on the deserted avenue.

Toby’s select vintage finds, photographed in Brooklyn, New York on Thursday, Sept. 24, 2020.

After greeting a passerby, who told him that she’ll be “right back” to look at his items, Toby told me he came back out in June, when he saw other vendors in the streets. We talked about the neighborhood post-quarantine, which he described as “not that different” save for the absence of tourists. When I asked him what he thought about New York’s handling of events over the last few months, he said that while he was content with statewide leadership, he was disgusted at the “extreme politicization of the disease” on the national level.

Many of Bushwick’s street vendors that depended on passerby customers, including Toby, played it safe and didn’t do business during strict lockdown. Since the beginning of summer, most of them have now returned. Thursday, Sept 24, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

As for how business was impacted, Toby was one of the lucky ones.

“I’m retired and I get a pension so financially, I could survive without this. But you know I just like it so much.”

In addition to records, books and jewelry, Toby also carries framed photos and other art. Here he poses by his table on Thursday, Sept. 24, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

Other small businesses in Bushwick whose livelihood depended on their sales were in a tighter bind. Brooklyn Vintage Company, nestled in the corner of Irving and Himrod streets, was barely a one-year old business before the crisis hit. The eclectic shop, known for housing a curated selection of vintage items that includes furniture, clothing, home goods, records and more, was closed for four months during the coronavirus, which severely impacted the financial standing of the walk-in dependent business.

But far from giving up, the owner Cat Varga immediately looked to adjust to the new norm.

“You turn and you pivot, and you adjust. We knew it wasn’t going to be an overnight thing,” said Varga when I asked her about her response to the government mandated shutdown of all nonessential businesses. “The only way we were going to be able to have any sales at all, was through Instagram.”

The team put a lot of effort in the following months to increase their online presence, and made the impressive feat of acquiring over 4,000 followers on Instagram. Varga also spoke about how community members supported the business during the pandemic – an example she gave was how people sent her messages whenever they liked something in her shop’s window.

“It was pretty key to keep us connected,” she said.

Though the online sales during quarantine didn’t measure up to pre-Covid profit margins, Varga wasn’t disheartened by the situation. She had faith in the purpose of her business, which centers on the more personal experience that vintage shopping affords people.

“There is a lot of reminiscing [with vintage], happy memories of families…vintage in general is satisfying a need. Everything now is online, cold and impersonal and people want more of that personal experience,” she said.

When I asked whether she applied for loans or programs set up to provide financial relief for small businesses, Varga says she didn’t even attempt to go through the process.

“Being a really new business was extremely challenging…and [the applications] were very bureaucratic. I didn’t really have trust in it.” She also mentioned how the loans given out to small businesses owners often paled in comparison to what the banks handling these loans were being paid, which she said, “didn’t set right with [her].”

But on the grander scale of how the virus was contained, Varga declared she was proud of New York, where she said people were generally “used to taking care of each other.” In regard to leadership, while she wished that Governor Cuomo and Mayor De Blasio had put out a more united front, she thought they handled the outbreak in New York “pretty well.” She did however qualify her answer saying that her views might be different than say, a first responder’s.

“I know it was very bad, and from a hospital standpoint, I can’t say what these leaders could have, should have, would have done better,” she said.

Varga’s comment rang true when I met David (not his real name), a biomedical equipment technician at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, who held a different view in regard to statewide response. When I asked David about the competence of the governor and mayor of New York, he answered bluntly, “Never mind those guys, they have no idea what the hell is going on.”

He then added, “Honestly if you really want to find out what’s going on, you would have to come into any hospital and see for yourself what the staff is doing.”

David is in charge of ensuring that all biomedical equipment, including ventilators, are working properly, which during the pandemic put him in the middle of the crisis and in close proximity to coronavirus patients. His recounts of the outbreak beginning in March are chilling – he said he knew from “day one” of the severity, as he watched all floors and departments of the hospital get overtaken by coronavirus patients.

The exterior of Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, one of the largest hospitals in the Bushwick area. During the height of the pandemic, the center was a regular reminder of the ongoing crisis to community members. Tuesday, Sept. 29, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

“I was getting here about 6 a.m. or 6:30 a.m. and you’ll hear code blue, which means you know, the patient has died. And it was absolute chaos. I would leave at 8 p.m.” he said, adding that the situation improved slightly, for the first time in June.

David was especially critical of the national leadership during the pandemic.

“They have no clue what’s going on…it’s all politics to them. Why would they worry? They could go to John Hopkins or the Mayo Clinic [if they were infected]” he said.

But one group of people David thought responded well, were the community members who adjusted to the new norms “fairly quickly.” However, he did complain of people sitting down next to him without a face mask – he thought they should have known it would be an endangerment to many vulnerable people besides him, given how David wore his hospital badge at all times.

When I asked him if he was worried about his own health, he told me sometimes he would overthink every contact he had with patients, to the point where he would start to question whether he had been as safe as he could be. But to jolt himself out of that state of mind, he thought about how he and his colleagues were “dealing with human life” and that inevitably “somebody had to do it.”

“Sometimes it’s overwhelming, and that’s when I come outside, smoke a cigarette and go back in and start all over again.”

The curbside parking of the Emergency Room at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center was regularly occupied by refrigerated white trucks, essentially used as makeshift morgues during the height of the crisis. Community members were often reminded of the tragic losses when passing by the grim sight. Tuesday, Sept. 29, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

When I asked him how he thought the hospital would fare in the face of a second wave of infections, he initially had an optimistic answer.

“Everybody learned. I think we could do a lot better and with a lot less lives lost.”

However, following a more in-depth discussion of national leaders, David voiced skepticism about current health systems ever benefitting the ordinary citizen. He pointed out how time and time again, we trust leaders to make actual changes, but given that it’s an “economic game”, he thought there was no point in believing them.

“I mean I will always see [and give them a chance] …but if they fail, I’m not surprised.”

He later posed the same question to me, leaving me to reflect on whether I want to get to the stage where I’m not surprised.

But David was certain about one thing: he needed to be at the hospital, doing what he does. When I asked him if he had any initial reservations about becoming an essential worker, he said he adjusted to the title quickly when he thought about how “any patient could’ve been [his] family member”. However, not everyone was willing to assume this heavy title – David told me one colleague refused to work on the floor, especially during the time when every floor had a patient suffering from the coronavirus.

“I mean, he had a family at home and he was worried,” he said about his colleague. Following a brief pause, he added, “but I have a family too.”

Similar to David, other essential workers in supermarkets and sanitation industries were asked to assume roles that put them in close proximity to crowds of people, at a time when it was known that people infected with the coronavirus could be asymptomatic.

When I asked Jose Jr. Diaz, who is a general manager at Key Foods in Bushwick, whether any employees, including himself, had any reservations showing up to work during peak coronavirus outbreak, he said “No, not at all.”

“My team and I realized we were essential and people needed us to supply food for them.”

The employees of Key Foods saw an unprecedented number of shoppers during the height of the pandemic in early spring. Now, the store is less packed and regaining some sense of the old normal, though all social distancing measures are still in place. Saturday, Sept. 26, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

However, he noted that unlike many others, he was worried as soon as he heard about the virus, even before it reached the United States.

“I had a mother who was sick. I was worried right away.” He later shared that his mother passed away due to the coronavirus but insisted that given the times and his essential role, he still believed he had no choice but to show up for work.

While it’s no hidden fact that grocery stores nationwide were presented with many challenges during the pandemic, it’s important to highlight how novel and at times, paradoxical these challenges seemed. When stores remained open during lockdowns nationwide, business was booming but tensions were running high on the interpersonal level. To ensure everyone’s safety, staff members had to work hard to enact new rules pertaining to social distancing and face coverings, while simultaneously dealing with long lines of anxious customers and shortness of supplies. At times, this led to heated exchanges between customers and supermarket employees, as was revealed by various videos that went viral in the last few months.

Jose Jr. Diaz, mentioned similar challenges at Key Foods – long waiting times, shortness of supplies and a sense of heightened tension, especially during the beginning of the pandemic – but commended his team and the community for their patience and cooperation. He also said he was cognizant of how badly it could have gone.

“I’m in a supermarket association, so I know a lot of owners, and they’ve had some bad instances [in their stores] but this community has been very good to us. And we try to be very good to them.”

One of the many signs at Key Foods, reminding people to stand apart when waiting in line. Saturday, Sept. 26, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

In terms of business, which he mentioned “doubled in size” during early months of the pandemic, he described how his biggest challenge was keeping up with demand, as wholesalers ran out of certain goods, leaving management scrambling to find other companies that could supply products in high demand, such as paper goods.

“Now we have a good amount of stock. We thought ahead this time and bought it in bulk,” says Diaz.

When I asked him if he was worried about another outbreak, Diaz said he wished for New York to remain healthy for a long time but that if we were in crisis mode again, that he and his team would be prepared to serve, just like the first time.

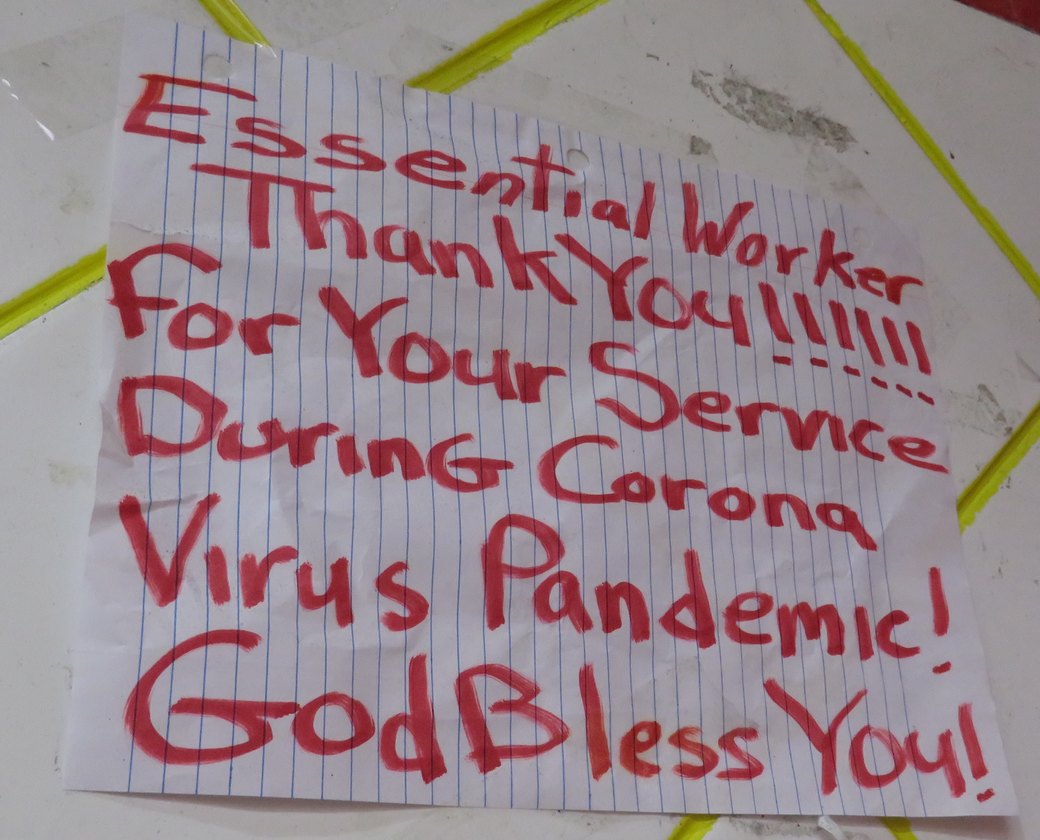

A message found on an announcement board at Key Foods in Bushwick. Like everywhere else, many essential workers in the community were met with gratitude and appreciation, especially during the early months of the pandemic. Saturday, Sept. 26, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

While grocery shops like Key Foods immediately qualified as essential establishments, there were many nonessential businesses that people used routinely, such as barber shops and particularly relevant to New Yorkers, laundromats, whose services were in high demand during lockdown. While these businesses did close in March, they were also some of the first to reopen.

Chen said that he first sensed real fear in the community, when his customers whom he usually met face to face when delivering their laundry, asked that he leave their hampers in the lobby or at the foot of the door, to minimize contact. He also told me people expressed their fears to him in early spring about opening their windows or going outside, especially when white trucks were parked at Wyckoff Medical Heights Center.

“The four big trucks, staying outside, you know they carry bodies. Everybody saw it…everybody was scared,” he said.

Ocean Laundromat is located only a few blocks away from the entrance to the Emergency Center at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center, where makeshift morgues were a familiar sight during early spring. Tuesday, Sept. 29, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

When I asked Chen what he thought about during lockdown, he said he was worried about his business. But he understood the importance of staying home, especially during that critical period.

“We had no choice [but to close]. With business and life, life first. Without life you don’t have business,” he said. “You have nothing actually,” he added, laughing.

The many sanitizing agents used to clean Ocean Laundromat. Friday, Sept. 25, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

Unlike Vargas, Chen applied for financial aid programs, but didn’t think the help was sufficient. As for how the state government handled the pandemic, Chen thought measures were taken too late.

“[New York’s] behavior was good, but not as good as people were expecting. Things happened in China first. Everything [in New York] was open so late, until the thing spread to the whole city and left so many people dead. I think this is a big lesson for everybody,” he said.

Simon Chen in front of his laundromat, Ocean Laundromat on Friday, Sept. 25, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York. Chen has been the owner of the business for the last two years.

And lessons are learned every day. While the coronavirus was initially thought of as a physical ailment with destructive economic impacts, as people reemerge from isolating lockdowns, the toll of the pandemic on the emotional and mental wellbeing of community members is also becoming evident. To cope with this specific challenge, people in Bushwick and around the world have been turning to art. While many Bushwickers have used their art to channel their personal experiences, some have also developed more interactive methods to give back to the community.

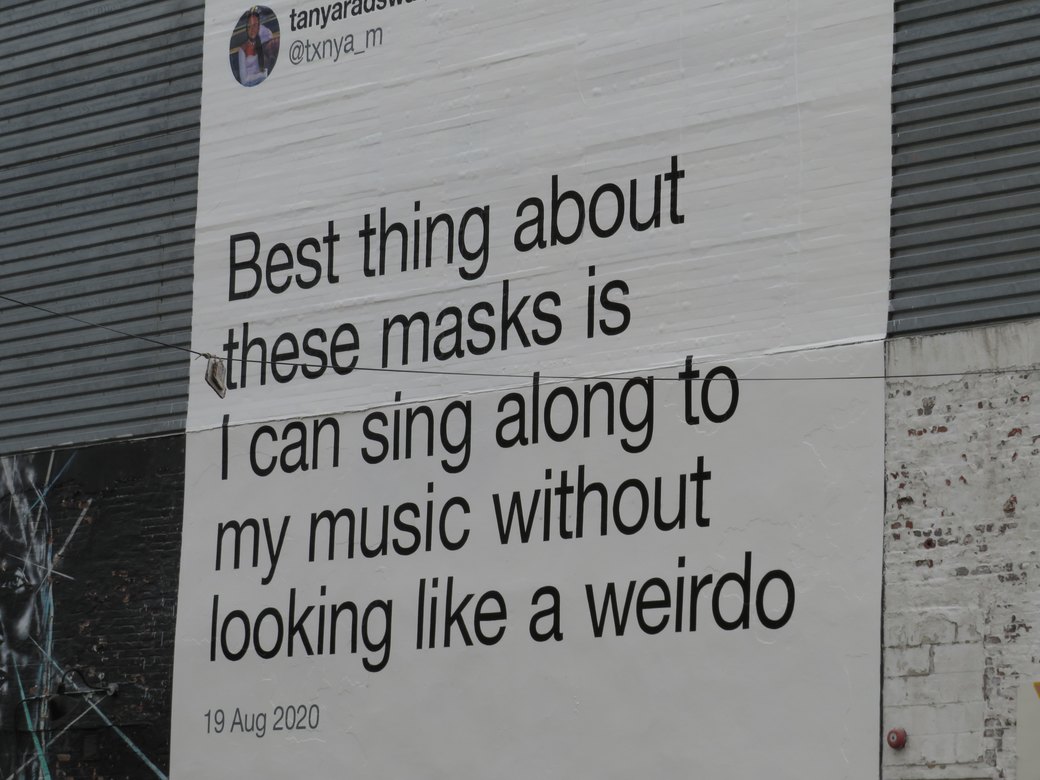

A billboard seen in Bushwick. The sign is one of the many new additions to the artistic landscape of the region. Photographed on Friday, Sept. 25, 2020 in Brooklyn, New York.

“My job, first and foremost, is to protect and heal in some small way,” says musician Matt Cross, whom I first encountered when he was performing for a small group at the Keep, a bar housing vintage antiques on Cypress Street. During both of his impromptu, socially distanced performances at the Keep’s outdoor patio, Cross was collaborating with other musicians and putting together surprisingly streamlined shows, given the lack of strict preparation.

Cross plays the electric guitar, gravitating toward music “that people can half listen to”, where listeners are allowed to be enjoying themselves, and no one feels the need to “shut up and listen.” His more laid-back attitude is also reflected in the way he talks about his music, which takes on many different genres, among them blues, rock & roll and jazz.

A photo obtained from the Instagram of Matt Cross (right), where he’s seen performing outdoors.

When I asked him how he first reacted to hearing about the pandemic, he said, “I’ve had waves of fear when it first started. I’ve got longstanding mental health struggles, so I knew this was going to be a thing.”

He mentioned that having mental health issues at a time of global health crisis and financial insecurity made him feel like he was in a “big game of cat and mouse, with a thousand cats.”

Fortunately, the “money cat” was less of a problem than he initially thought. While Cross did suffer the financial consequences of being laid off the East Village Social, where he was booking steady gigs, he applied to government aid programs and temporarily left Bushwick to stay afloat. He also shared he has a side business of buying and selling blankets, a lucrative trade he’s thinking about taking with him to Nashville, his next possible choice of residence.

For now, he’s performing for himself, and for anyone else who’ll listen.

“I also play on some sidewalks” he says, “It makes my job easy…I just play a simple song, not even sing it, and people walk by and smile and wave. And you know they’ve liked it.”

When I asked how these past few months affected his art, Cross simply said, “It validated it.”

For more news, sign up for Bushwick Daily’s newsletter.

Join the fight to save local journalism by becoming a paid subscriber.