When Carlotta Williams moved to Linden Street in the late 1980s, the neighborhood was different from today’s Bushwick. The bright corner coffee shop didn’t exist. The renovated townhouse down the street wasn’t listed for over $2.1 million. But despite the signs of development and modernization, Linden Street has held steadfast to its past.

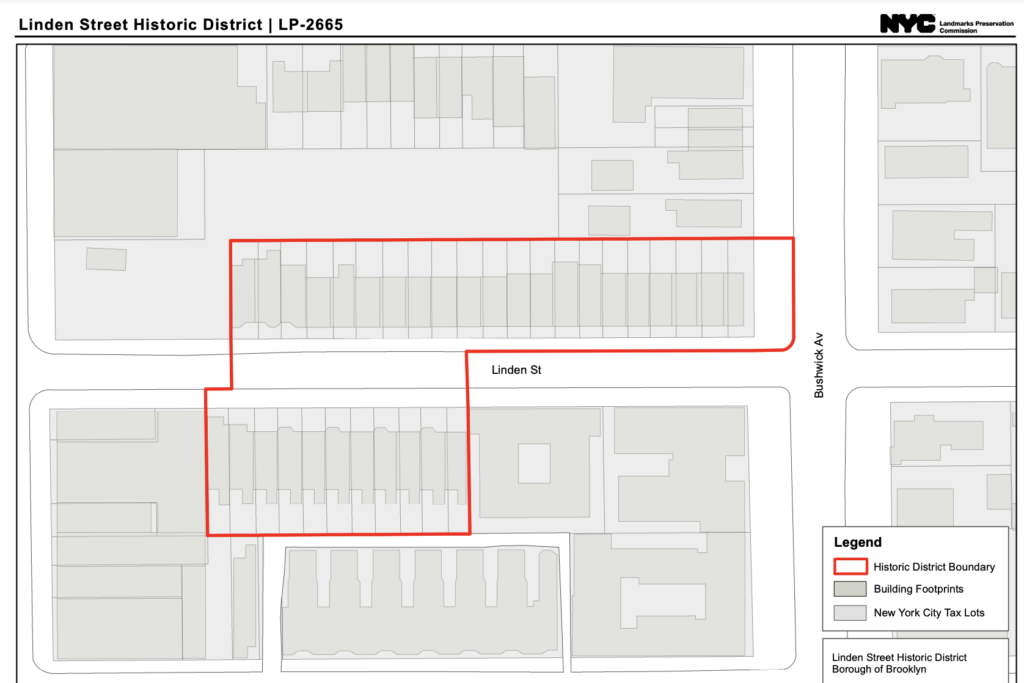

One block of Linden Street, from Broadway to Bushwick Avenue has remained virtually unchanged—on the outside, at least. Williams had watched as her neighbors grew up and raised families in the same centuries-old brownstones. Now, thanks to a unanimous vote from the Landmarks Preservation Commission this past May, the block of 32 brick and brownstones will be preserved indefinitely as part of Bushwick’s very first historic district.

Locals say the homes display century-old architecture that has stood the test of time and will now receive reinforced protections. “I think we are all honored and proud,” said Williams, now a 71-year-old former community board member. “We’ve been trying for this for years.”

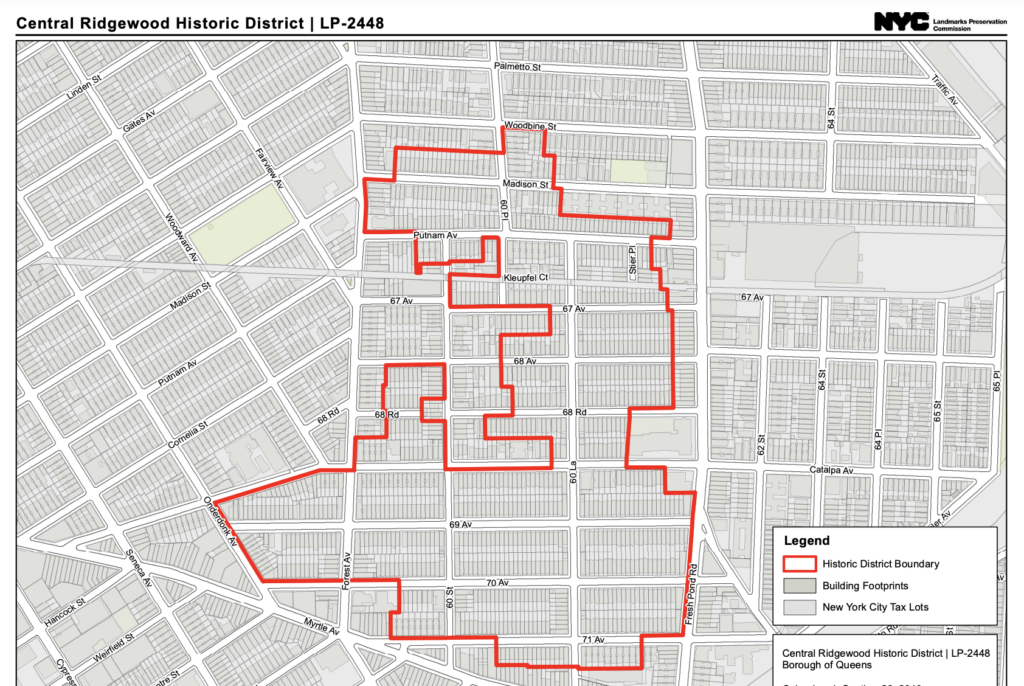

But the process wasn’t easy. Swaths of nearby Ridgewood started to receive such designations in 2000 — the most recent, a 990 building, 40-block district there was designated in 2014 — and most of the Upper West Side was designated as a historic district as early as 1990. Williams said she’s been pushing for the same recognition in Bushwick for years.

Local city council representative Jennifer Gutiérrez said this was because Bushwick was long not taken seriously by the commission.

“Bushwick is still a majority black and brown [neighborhood]” Gutiérrez said. “And it doesn’t scream Upper West Side historic district in the way that LPC traditionally had done things.”

A 2020 study found that residents living in neighborhoods the commission deems “historic” are more likely to be white and have higher incomes and levels of education than in the rest of the city. In 2010, the average tract of land in one of the city’s historic districts was 80% white and 90% college-educated, compared to just 43% white and 33% college-educated in the rest of the city.

For a district to get designated, it must be evaluated by the landmark commission. First, an area is identified—sometimes through public suggestions—and then assessed. If they decide the idea “may merit” consideration, it is added to the agency’s survey list. After the commission’s staff present their findings, they vote on whether to schedule a public hearing, often featuring testimony from residents. Following the hearing, the commission then votes again.

Gutiérrez, who has watched local mansions turn into luxury development before her eyes, said the designation was a “really big deal.” Now, she’s pushing for even more historic districts in Bushwick.

“Ensuring equity and inclusion in designations has been a priority for LPC chair Sarah Caroll,” The commission said in a statement. “During her tenure the commission has focused considerable resources to prioritize designations that represent New York City’s diversity and designations in areas less represented by landmarks, a commitment to equity that is reflected in the agency’s recent designations.”

For others, however, historic designations can offer more risks than rewards.

Adam Millsap, for instance, believes that they can ruin cities. A senior fellow at billionaire Charles Koch’s Stand Together Trust, he wrote for Forbes in 2019 that “today, in cities around the country entire neighborhoods of marginal historical value are frozen in time, hindering the ability of cities and their residents to adjust their built environments in response to changing economic circumstances.”

“You tend to see housing prices go up in historic districts,” Millsap said in an interview.

Some are concerned about this spike. A key concern is the spike of housing prices. When a neighborhood perpetually maintains its look and character, affluent prospective homeowners that value that aesthetic could begin buying the neighborhood. This could impact the prices of surrounding areas and, in turn, push out its working class residents.

People today need cheaper ways to get adequate housing, said Millsap: “The world belongs to the living.” Yet despite concerns that historic districts will increase housing prices and lead to a change in demographics, the landmark commission does not track any of this data.

The commission does, however, conduct “extensive outreach to property owners at every stage of the designation process.” In a statement, the agency also noted that it does not prevent owners from making changes but rather works with them to ensure that planned changes are appropriate to the building’s style.

Some worry about costs to uphold the external appearance. Millsap encouraged all Bushwick residents to start asking questions and to investigate the specifics on what they can or cannot do to their buildings.

He’s not the only one wary of historic districts.

The 2020 study found that although racial composition seems not to change, “when census tracts become historic districts, the share of college-educated residents increases, as does the median income and homeownership rates.”

The report warns that, “In order to preserve the diverse history of places like New York City and to ensure that the rich community landscapes reflecting this diverse history are preserved, historic preservation policies should pay explicit attention to whose neighborhoods are designated and who bears the benefits and burdens of those designations.”

But an uptick in property prices in Bushwick–and the corresponding influx of wealthier, whiter residents—is not new. And it’s too early to tell whether its new historic designation will accelerate this trend, let alone impact it at all.

“Bushwick and now Ridgewood have seen some of the highest rates of rent go up in a short amount of time, and certainly then, landmarking didn’t have very much to say about that,” said Gutiérrez. Developers have transformed Bushwick’s streets for years—historic designation or not.

This has played a part in Bushwick’s ongoing housing crisis. From 2009 to 2017, median rents jumped from $961 to $1460 per month and the white population almost doubled. Today, popular renting websites like Zumper estimate the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the neighborhood at $2850.

The housing crisis has already displaced thousands of Latinos in North Brooklyn, said Gutiérrez.

“So I don’t see a world where there are two things up at the table, which is like let’s create another historic building or build this massive 100% affordable building,” she said.

John Palladino, a 53 year-old-native New Yorker who co-owns a local coffee shop called Cup of Brooklyn, has seen the increase in rent prices firsthand. Since moving to the area fifteen years ago, he has watched a flood of developers construct high rises where he said young people need “eight roommates just to pay rent.”

But Palladino hopes that the commission continues recognizing more of Bushwick. “There’s a lot of beauty to Brooklyn that people don’t see,” he said. “I do see it as a positive thing. Then contractors—rather than destroy it or knock it down—will maybe try to give it life again.”

Gutiérrez said there are ways the commission could expand support to residents.

“I think this movement is being led by a community and by other property owners who have been in Bushwick a good amount of time and understand the tensions and understand the realities,” she said. “I have confidence that they will continue to work together to ensure that yeah, we’re getting landmarked, but that we’re still very much Bushwick regardless of a historic district.”

There may be decades worth of history buried deep in Bushwick’s bricks. Buildings hold endless history and archive bygone eras. But it will always be the residents that preserve those stories for lifetimes.

“There are people on this block, all these people that have been born here and we don’t want them to get pushed out,” said Williams. “It takes dedication to persevere.”

Top courtesy of Google Maps.

For more news, sign up for Bushwick Daily’s newsletter.

Join the fight to save local journalism by becoming a paid subscriber