“Transplants,” the latest multi-artist show from Bushwick gallery Amos Eno, is a show about what it means to arrive, leave, and change ourselves and our environments.

This makes the show inseparable from the political and socioeconomic background against which its artists move, evolve, and come to terms with their worlds. Ellen Sturm Niz, who curated the show, has assembled a collection that asks who can and should transform or evolve in New York City and the world at large.

“When I was thinking of issues that are top of mind for people in the United States and other countries right now, it’s trans rights, it’s immigrant rights, it’s a lot of social issues revolving around people being displaced,” Niz told me before the opening. “‘Transplant,’ as a word, applies to so many ways of being displaced,” she said.

The broadness of Niz’s theme gave the artists a great deal of freedom to explore displacement from a range of angles. The works from the 43 local artists in the show — 22 of whom are based in various parts of Brooklyn — create a dialogue amongst themselves and ask the viewer to reflect on the different motivations and freedoms among the “transplants” inhabiting New York today.

Adrians Black Varella’s photographs “Transbodies” and “Transomas,” for example, stab right at the heart of the ongoing campaign to demonize, criminalize, and even outright kill transgender people by entertaining the debate over whether they have rights to live and love which has steadily crept into the national consciousness as the latest in a long line of American moral panics.

“Transomas” (from soma, Greek for “body”) is also positioned as both connected and opposed to the academic realm, where chromosome charts and archaic terms like soma might make an appearance.

Varella’s title choices are also a key point from which the dialogue between the two pieces show how the dehumanization of trans people can take place even in contexts and discourses that have an ostensibly objective and detached perspective.

Both photos present a treatment of human bodies. In “Transbodies,” Varella shows them treated with tenderness in their interactions with each other. “Transomas,” however, highlights an alternative treatment of those bodies, medicalizing and essentializing them — though Varella resists and challenges that reading by modifying the chromosome chart with white correction fluid.

In each photo, the bodies are presumed to be, at least, physically safe. Still, “Transomas” cannot help but recall the systemic transphobia of healthcare as an institution in the United States, despite the efforts of advocacy groups to highlight and address that discrimination.

But the show also poses the question: Is Bushwick a safe haven for trans people?

It certainly has that reputation in popular culture — in an interview with the queer singer Kim Petras, a writer at the Condé Nast publication Them once characterized Bushwick as “a neighborhood in Brooklyn where non-binary stereotypes are born.” But while there might be a greater number of spaces, relative to other cities, that are, at least on paper, welcoming to the trans community in Northern Brooklyn, the larger intersection of trans identities with issues of race and class makes one wonder if it is accurate to characterize a community as trans-friendly when the average studio rents for $2,500 per month and trans people disproportionally face poverty.

Or, to approach that question squarely from the theme of Niz’s “Transplants”: What is the point of creating a small, expensive, trans-friendly island in the middle of a rising sea of anti-trans legislation?

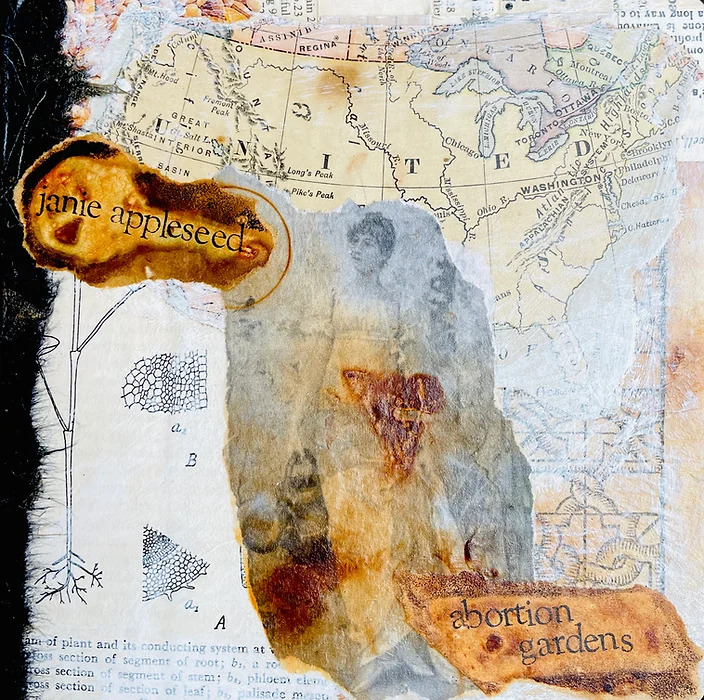

A similar question is posed by Alexandria Jameson’s “Janey Appleseed: The Abortion Garden Book,” a collage that comments on how the right to bodily autonomy for individuals capable of giving birth can and must be preserved, even if that right must be literally dug out of the soil. Again, it seems necessary to ask, given the context of the show: Who is allowed to transplant themselves, and who must dig where they are?

What about individuals who transplant themselves for reasons we might consider more mundane than escaping bigotry; those whose socioeconomic position allowed them to transplant at will because of a job or relationship or because of a dream or a whim or a wish to get away brought them here?

Transplanting blood or an organ is an undeniably violent experience: something familiar, but nonetheless damaging or distressing, must be ripped or siphoned out, to be replaced by something else. The same might be said for transplanting our whole self from one community and culture to another. Why is it that transplants insist on that pain?

Another collage, Fan Yu’s “Pretend Happiness 2,” suggests one answer by peeling back the veneer covering that pain by seeming to ask: “There is glamor to be found in New York and in Bushwick, if you can find and gain acceptance into the right crowd. Why not play a little make believe to ensure that happens?”

“Oro,” Nathalie Basoski’s haunting image of encircled dancers with dark silhouettes among them, takes a slightly different tack and directs attention to what may have been left behind.

Basoski’s process, according to an artist statement provided for the show, involves the reconceptualization and reworking of digital images to create narratives in retrospect. The process invokes the way re-remembering frequently alters those memories, with new narratives and new understandings of ourselves arising from the alterations. Whether through temporal or geographic distance, the details of our lives change.

Elsewhere, Tana Oshima’s “I am that shape again, #5” also recognizes the impermanence of the self in transit, with the single floating figure tossed between abstractions reminiscent of waves and clouds. Oshima’s title choice, however, hints at an opposing notion underlying her work.

As the self drifts between cultures, locations, and life stages, it also is the self which remains constant. It may perform a certain role to fit a mold for the sake of protection against perceived danger, or it may change memories for the sake of preserving what it has deemed essential truths. Still, the core of the self remains. Despite transplantation, despite new shapes and new attitudes and new environments, the self remains.

“Transplants” runs from July 14 to 29. Amos Eno, located at 56 Bogart Street, is open between 12 and 6 p.m. from Thursday to Sunday.

Images courtesy of Amos Eno Gallery.

For more news, sign up for Bushwick Daily’s newsletter.

Join the fight to save local journalism by becoming a paid subscriber