The brochure for Banksy’s Dimaland touts “a festival of art, amusements and entry-level anarchism.” Weston-super-Mare, the somewhat downcast seaside resort town near his hometown of Bristol, England, provides a big canvas for a small town art intervention. Banksy, not known to drop a theme, transplants a Disney-styled urban imagery, to create a contextually odd art experiment.

In Fall 2013, Banksy decamped to New York City for a month-long artist residency. Each morning a photograph of a new, unlocated piece was posted to his website spawning a frantic, citywide scavenger hunt to locate, photograph and in some cases appropriate the new work.

Much of the art at Dismaland is displayed in a traditional gallery setting. The Grim Reaper in a bumper car formerly unveiled during his New York residency, makes a back-from-the-dead appearance. However, the new context seems less political and more like a haunted playland effect. The park works hard to create a mash up of art and urban detritus. The Tiki bar might have been plucked from the yard at Secret Project Robot in Bushwick. As a theme park, it is less dismal than bemusing, and portrays ambiguous voices, sometimes dark and funny, sometimes beautiful and depressing.

I asked a few residents of Weston-super-Mare for their impressions – most responded, “It’s different.” A local paper printed free invites for the opening party, but people passing by the huge “Dismaland” sign could still be seen staring at it asking questions, perplexed. Some more excitedly talked about reselling merch on Ebay for big profits.

Getting in was no mean feat. After several failed attempts on the (gag?) website, we found tickets on a scalper Stub Hub; the tickets were marked “NO RESALE.” Security at the gate was unpleasant and bemusing – we got to keep our shoes and belts, but were searched by ‘real’ security for spray cans and sharpies in case we planned to do our own tagging. Real security lines funneled into fake security lines replete with metal detectors and a courtesy pat down. A sign warned that I was being filmed and I had the, “Oh cool, I might be on MTV!” feeling mixed with the “Damn, it’s CCTV!” feeling.

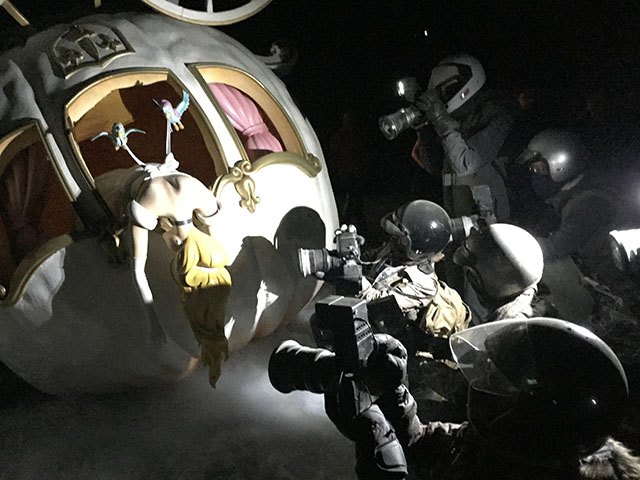

Reminiscent of Williamsburg’s McCarren Pool, Dismaland is housed at the pier’s former Tropicana lido building and now defunct swimming pool. The pool, partially refilled resembles a moat in front of Cinderella’s ‘haunted’ palace. The park’s main attraction, a mangled Cinderella hangs off her overturned pumpkin carriage while papparazi (policemen in riot gear) create a strobe of flashes and snaps. For me, it’s not Lady Di; it’s the party I got dragged to at the Bushwick Church. Strobes, trashed princes and princesses, cameras everywhere. I wondered if Banksy had been anonymously hitting the Shade parties.

At the end of the day, ‘when the park shut down’ there was a serious message about sustainability. The event served no meat, non-dismal workers sat in a tent with pamphlets on anarchism, gender identity, and fascism. Where the dystopian Dismaland depicts artists clashing with governments and corporations with short-term profit motivated solutions for the planet, Bushwick, at least for now, is not the sinister art experiment or a themed disney town. The creative inspiration for artists to change the neighborhood is real, though the ferris wheel would fit right in.