Community-supported agriculture (CSA) can be a wonderful resource, providing farmers with steady income and consumers with locally-produced food. One of the few drawbacks, however, is that they often cost a hefty upfront sum. Many CSAs cost $300-500 for a single season. Spread out over several months, it’s not much to pay for the privilege of local produce delivered on a regular schedule, but it’s not a socioeconomically inclusive model. To help alleviate this issue, Bushwick-based community organization RiseBoro Community Partnership will launch a new CSA program this July with a payment structure better suited to lower-income residents.

Come July, RiseBoro will team up with local farmers as well as a local food cooperative known as the Brooklyn Packers to create a kind of à la carte CSA – one that customers can purchase on a week-by-week basis. Prompted by the results of a Community Food and Health survey that RiseBoro administered last March, the organization aims to address food insecurity in Bushwick and other Brooklyn neighborhoods. Half of the 1,140 people surveyed considered the availability of locally-produced food where they shop to be important, and 15 percent expressed an interest in eating more fruits and vegetables. On top of this, close to half felt a need for the stores they buy food from to accept SNAP. RiseBoro farmers markets already take SNAP as well as other supplemental payment options like EBT and Health, and all of these can be used to pay for the CSA.

The CSA’s organizer, Ashleigh Eubanks, is an ideal person to spearhead this program. No stranger to food justice work, Eubanks formerly worked for the Communities for Healthy Food Initiative at Bed-Stuy’s NEBHDCo. RiseBoro already offered health and wellness programs Bushwick Cooks, Bushwick Grows!, and Wellness Rising, but hoped to develop a stronger food justice framework. The organization hired Eubanks along with her former NEBHDCo supervisor Bianca Bockman to do the continued work of improving food security in the area.

According to Eubanks, the CSA will take things a step further by making local food even cheaper and easier to access, while still “keeping money in the pockets of community members” by partnering with organizations like the Brooklyn Packers. The aim is to make sure farmers get paid fairly, while keeping prices accessible for lower-income residents.

On a larger scale, Eubanks hopes to change the conversation around the food industry. The main injustice of the system, she said, is that it harms both the people forced to buy food that is “unhealthy and highly processed” and the people who work in the industry, many of whom are subject to poor working conditions and paid low wages. She feels that the burden of that injustice shouldn’t be put on consumers.

One of the benefits of having a nonprofit as an intermediary, Eubanks told Bushwick Daily, is that nonprofits are able to absorb part of the overall cost of the product. The Brooklyn Packers’ product, Brooklyn Supported Agriculture (BSA) costs $25 a week. Through the RiseBoro CSA, the cost can be lowered to $20, increasing its accessibility even further. The other benefit of this model is that farmers can still make a livable profit. “Nobody is losing anything,” Eubanks said.

Because RiseBoro hopes to scale the CSA sustainably, the first season will take the form of a pilot. RiseBoro will keep to a manageable 20 customers by advertising it internally to its more than 2,000 employees, many of whom are too busy to visit the farmers market on a regular basis, Eubanks said. The CSA will also run year-round, as opposed to the farmers markets, which only run from mid-May to early December.

According to Eubanks, customers won’t need to sign a binding agreement to purchase the CSA. The commitment will look more like “trust and hope,” though they may eventually draw up a loose contract.

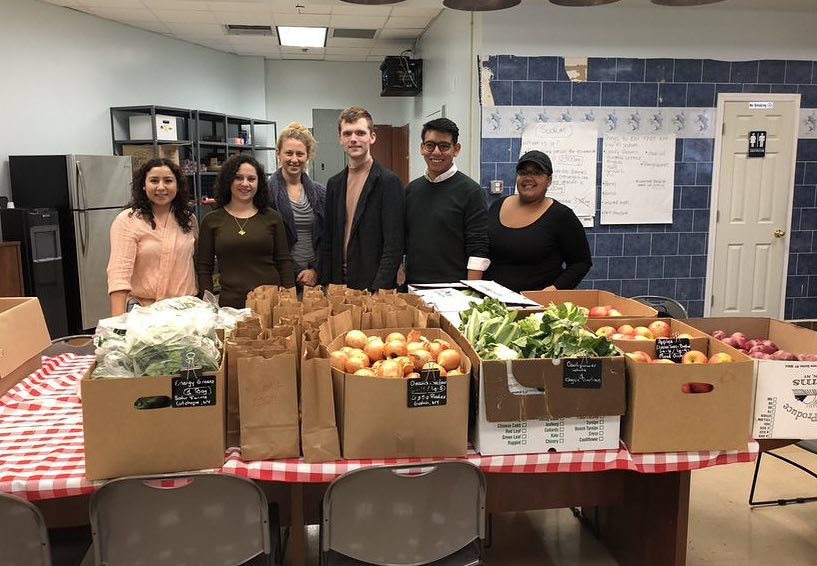

All photos courtesy of Riseboro

For more news, sign up for Bushwick Daily’s newsletter.