By Terri Ciccone

Big collectors never come to Bushwick. Or do they?

Two paintings sized 11″ x 14″ and priced at $12,000 were sold two weeks ago at The Bogart Salon (a third similar one is on reserve). One of the many new galleries that have sprung up in the past year at the 56 Bogart building can be rightfully proud. While $12,000 price tag on a painting might not raise many eyebrows in Chelsea, they have shaken the common opinion that big collectors never come to Bushwick.

One of the greatest contemporary artists and collectors in America who wishes to remain anonymous saw the potential in Royce Weatherly’s paintings, and didn’t hesitate a second. “These works are special” says gallery director Peter Hopkins regarding Royce Weatherly’s paintings currently exhibited in a group show titled Modesty: A Policy at The Bogart Salon through May 28th.

“Everything that we have worked for is “now”. It will either work, or it won’t work but it will happen now,” said Peter Hopkins referring to his predictions that the bigger collectors can and will come to Bushwick. During the panel discussions Confronting Bushwick held back in January, and more recently this past March at Capital and its Discontents, both organized by his gallery, the panelists and the audience alike were mostly skeptical that this would ever happen.

“These sales have helped change Royce’s life, my gallery, and mybe even Bushwick. This one small thing, that moment, everything may have turned on it,” says Peter.

The Bushwick Game

But is the sale of one or two paintings enough to draw the attention to the entire neighborhood? Why come to Bushwick if you can see something similar and just as great in Manhattan? Peter Hopkins believes that he has found a model that changes the way we think of conventional gallery shows. “If you create a game that is so different that they [collectors and museum directors] can’t not come, they will come. If you give them no reason to come, they won’t, it can not be just another thing they can see somewhere else…. The model for me has always been to sell work at a much higher level, create a game that’s so open and connective that people say ‘What the hell is going on out there?’ come out, see the space, then ask about the work that we might be selling, at price points much higher than the Bushwick model. This was the first show that I tested it.”

When Hopkins references “the game” he is referring not only to a series of exciting events held at the gallery. He is also talking about a “game” with the best intentions and sense of the word. The game is played as not only a way of standing out from the crowd, but also to show that Bushwick is different, more playful, connective, and by being this way can help gain the attention of people who might be looking for new work in other neighborhoods. At The Bogart Salon, Hopkins holds notable panel discussions; he had a live recreation of a Manet painting; and soon is filming a Bolywood style soap opera in the gallery about the perils of the art world for young women.

The plan continues – in between these events, he shows “really precise painting shows that might not show up anywhere else,” a method that sounds simple enough but that he has been slowly developing over his 30 years of being an artist and seeing firsthand what the art world can’t or won’t show. That is another beauty of Bushwick. The slow evolution of paintings, plans and models that can happen here, whereas in other spaces, the norm is a turn over that must be as quick as a flash in the pan.

Royce Weatherly’s slow art

Royce Weatherly’s hand can be compared to Vermeer, and his mind to Matisse. After a 12-year painting hiatus, Royce produced a work that caught the very notable attention of major collectors. What makes Royce’s work so enticing is the arc of time in which he creates a work. Many young Bushwick residents will be middle aged and perhaps have moved on from the neighborhood by the time Royce’s work is “finished,” for a key element in many of his paintings, is age, both in the deliberate fashion his paintings take to produce, but also in the arc of their “completion.”

A painting hanging on the north wall of the gallery Untitled (Black Walnuts #1) has been created in 1994. Another work of what looks like brown flaking or cracked glass sits in the middle of a lighter brown ring. This painting is so much more than meets the eye, and is not for sale, because it won’t be complete until about the year 2050. This painting is as close to a living object as something in a frame can get. It’s mounted on top of what used to be a prototype for a Richard Prince painting, taken to be destroyed in the basement of the Barbara Gladstone Gallery (Royce’s former place of employment) and is held together only by a simple plain frame. The ring in the middle is grease, and the grease will continue to slowly spread, and gently eat away at the square in the middle, causing the brown flakes to fall and gather along the bottom of the frame. The brown grease will continue to grow and fill the frame with its earthly color.

“In a way, Royce represents the kind of person who Bushwick should theoretically be here to represent,” said Hopkins after talking about this painting as if it were a precious artifact that has been buried for years. “He’s 54-years-old, he’s shown all around the world, but no one could wait for him. I could.”

The paintings that are sparking the most interest however, hang on another wall perpendicular to this piece. We see two paintings of walnuts, one is dark, and yellowing with the years, and the other is bright, painted in the exact same way only lit from an opposite direction. The paintings emphasize the negative space, shadows and light, proving what isn’t there is just as important as what is. The viewer will have to patiently wait for the bright one to also become beautifully dim.

A painting Untitled (Work Lights) of the type of lights you might see on a construction site, glowing in a dark space. The lights are painted with such precision that this work can easily be mistaken for a photograph. But like so many works, the mood in this painting is what makes it come to life. The overhead lights are actually the lights that hang in Royce’s basement in New Jersey, where he paints. This is his studio now after his break from painting. The hiatus came from simply the everyday progression of life as the culprit (moving to the suburbs, buying a home, supporting a family, etc.) The painting appears to be created at a time where hope may have been lost. The dark basement is hardly visible beyond the two lights, except for a small shining orb in the distance, just barely illuminating a sliver of a staircase, perhaps revealing a glimmer of hope, a way out.

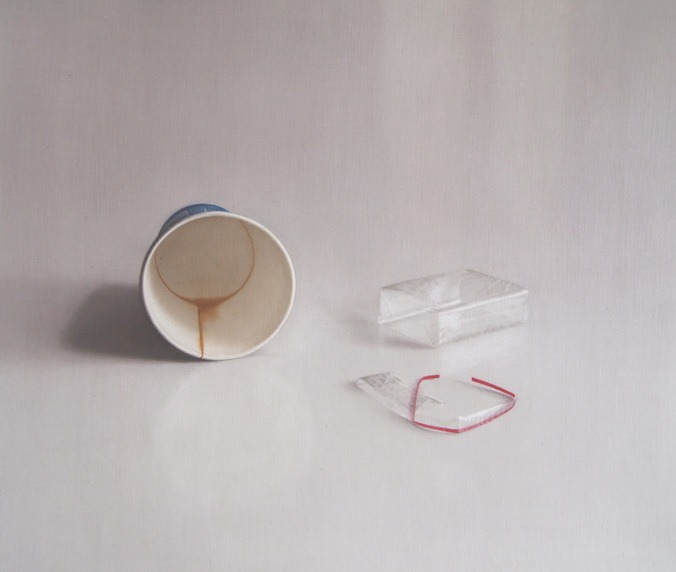

Perhaps the somber tone of this painting is what makes the next one in the series so inspiring. Untitled (Bupkis) is bright, and simple in its objects but complicated in almost every other way. On a white background filled to the brim with shadows and light, an empty coffee cup lays on its side. It’s beautiful circular geometry is balanced by its dark blue color, and drop of brown liquid leaking subtly at the back. Next to it lays the plastic packaging of a cigarette carton, painted with a delicacy and precision comparable to the way Botticelli painted veils on the Madonna. Both packages are empty, but there is nothing empty or somber about this painting at all. It’s almost joyful in that these two empty objects say something is coming, I’m back, I’m moving.

“I think I’m lucky. Its hard to back and out and come back into it again,” said the artist as he explained what may have sparked creating these paintings after such a long period of time. “Its kind of nerve wracking, you’re not sure if your ideas are any good… But hang onto your ideas and pay attention to what you know.”