Sara MacNeil

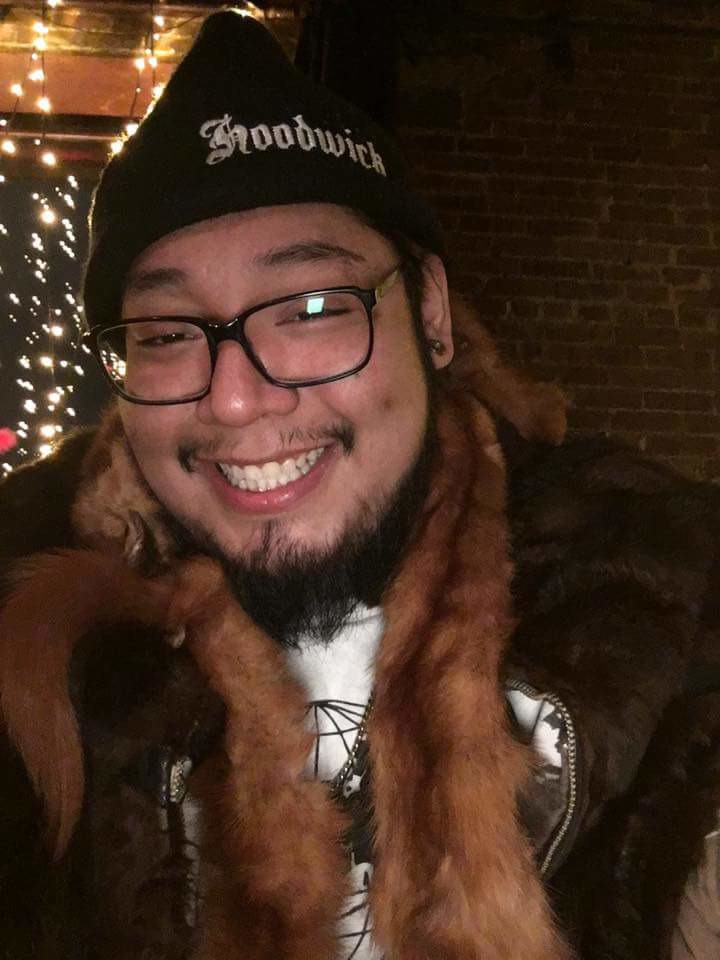

Graffiti artist and entrepreneur Ulysses Calixto, who died of a heart attack at age 26 on March 22, spray painted his nickname “Vato” on rooftops, abandoned trucks and buildings all over Bushwick. A tattooed, hefty man with a baby face, he spent his days tagging up the neighborhood while designing logos for his brand, Hoodwick.

The Jefferson Street native’s friends idolized and tagged along after Calixto.

“He was charismatic to a point where kids would just follow him around waiting on the next thing that would come out of his mouth,” his neighbor David Medina said.

Medina knew Calixto as a five-year-old who roamed the streets demanding people call him “Mafia.” When adult Calixto came out with his brand, he gave Medina a pocketknife engraved with the Hoodwick logo. Someone offered to buy it, but he keeps it in a dresser drawer, untouched.

Calixto’s sister, Judy Andon, said Calixto loved Mexican culture and painted Day of the Dead skulls as a young artist. His Vato moniker came from the L.A. Chicano gang in the movie “Blood In, Blood Out” she said.

From an early age, Calixto scorned societal expectations. Inspired by a video game about a rookie graffiti artist who tagged as a way to stand up for self-expression, he spray-painted the walls of his high school.

“Ulysses and his friends would all go and bomb whatever they could. He earned his chops there,” said Seth Failla, Calixto’s high school art teacher. Failla said the contradiction between Calixto’s bold and simple brand design and his colorful, lucid graffiti aesthetic reflected his nonconformist personality.

Calixto’s parents, Galo Calixto and Guadalupe Tlatelpa, immigrated to the U.S. from Puebla, Mexico, when they were 18. Tlatelpa said Calixto was an altar boy for three years and helped her organize Virgin of Guadalupe Day feasts for the church.

An old photograph shows Calixto in a striped button-up shirt, khaki pants, glasses and a military haircut.

“I’m sure he burned that outfit at some point in his transition to becoming a superstar of the hood,” Medina said.

After high school, Calixto ditched the business-casual look for a Ski ‘92 Suicide Jacket and bought a tattoo gun. He practiced tattooing on his friends in his parents’ basement, which also served as his art studio.

Calixto’s polished smile caught the attention of the Sunday Times Lifestyle Magazine in 2014. “He has all the trappings of a New York grillz wearer: tattoos, flatcap and a graffiti alias, Vato,” Rob Scher wrote. “Speak with him briefly though, and his knowledge, wit and charm belie this hood façade.”

Calixto earned an associate degree in graphic design and multimedia from Borough of Manhattan Community College. In 2012, he was a regular contributor to 12ozprophet.com, a street art website for which he reviewed art openings and zines.

Calixto was known as a family man, and had a full back tattoo that said “Mi Familia” and included the names of deceased family members. Calixto also tattooed the Virgin of Guadalupe onto his arm in honor of his mother, his sister said.

“Everything he was doing work-wise with his brand was to eventually be able to provide my parents a better living so they could retire and not worry about money,” Andon said.

Calixto has been laid to rest in Puebla, Mexico, joining much of his family already interred there.

The respect Calixto gained in the graffiti scene can be seen at Myrtle Avenue and Troutman Street where a large-scale mural of his face was painted shortly after his passing.

He will be remembered for welcoming and positively influencing those who had the fortune to meet him, his sister said.

“My brother, being so young, impacted so many people in so many ways through his art and his character,” said Andon. “It brings my family comfort that perhaps that was his mission in life.”